|

|

The Point of No Return Wilde Gallery, Basel September 02 - November 04, 2022

You can find the catalog at this link:

Wilde is pleased to present mounir fatmi: The Point of No Return, the artist’s first solo exhibition in Basel and his third with the gallery. The exhibition addresses a world invaded by information where everything revolves around data, graphics, and symbols. These same graphics, complex and incomprehensible, synthesize and completely change our relationship to reality. The exhibition asks, have we become mere numbers to a data-hungry global computer machine?

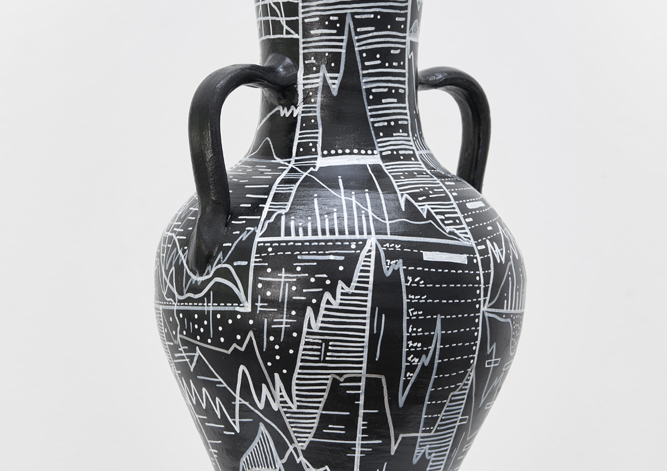

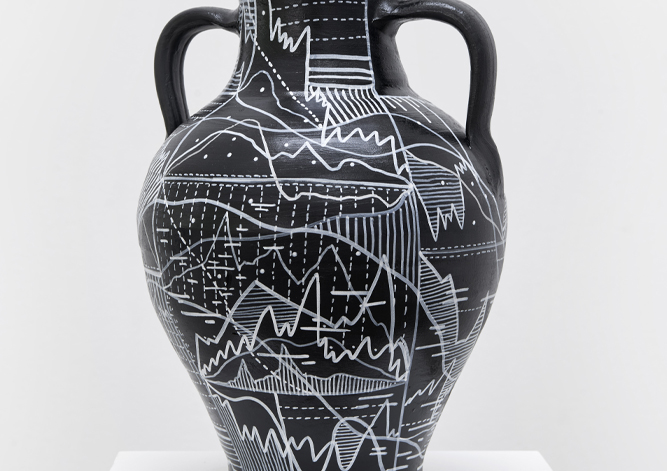

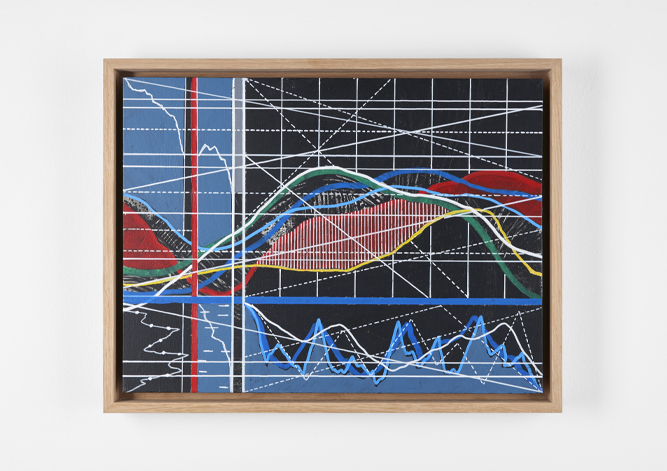

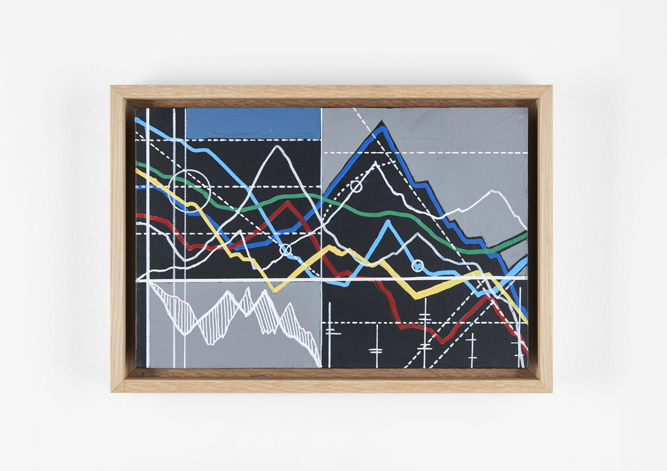

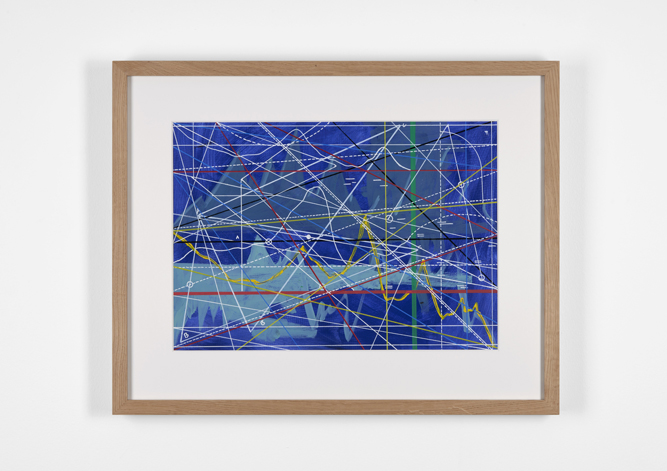

In dealing with these questions, the artist returned to the paintings, drawings, and ceramics that encompass a large portion of the exhibition. Since the start of his artistic career, mounir fatmi has been interested in language in all its forms, from Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets to Arabic calligraphy and computer coding languages. In 2014, mounir fatmi first started exploring the connections between a graphic language inspired by Arabic calligraphy and the visual language of economics. By painting stock market graphs, either in black and white or using primary colors evocative of computer programs, fatmi attempts to decipher this modern, omnipresent, and, to the layman, impenetrable language that nonetheless weighs heavily on our daily lives. The ubiquity of graphs, whether on television, in newspapers, or online, could be graphs of anything: the evolution of an epidemic, a study of the fauna of a mangrove, Tesla share prices. In an era of quantified information that feeds AI, we as audiences still do not understand these abstruse mathematical algorithms.

According to mounir fatmi, “To understand the world, one must not only measure the pulse of the financial markets but also of the flea markets.” Market influences affect everyone, from how one eats to how one gets to work. fatmi’s new series of sculptures, Dark, Dark, Dark, exemplifies this. Painted on ceramic amphorae and dinner bowls are graphic images charting economic ups and downs. The coldness of the graphics conceals their actual consequences on the world of the living: how much energy one can consume and thus expend.

Like the ticker tape of the Stock Exchange or scrolling through the continuous news cycle, the video Speed City sets a constant movement of skyscrapers in motion. The oldest Arabic font, Kufik, forms the building blocks of the city. Language is quite literally constructing a city. The work reflects the rapid urbanization of the Middle East, where cities are erected out of the desert, leaving little time for reflection. This notion of a fundamental instability, significant to mounir fatmi’s work, evokes the imagery associated with the tower of Babel, often represented as incomplete and imminently destructible, anything that marks the fragility of the construct as opposed to the vain architectural completion indulged in by the architects and backers of world megalopolises.

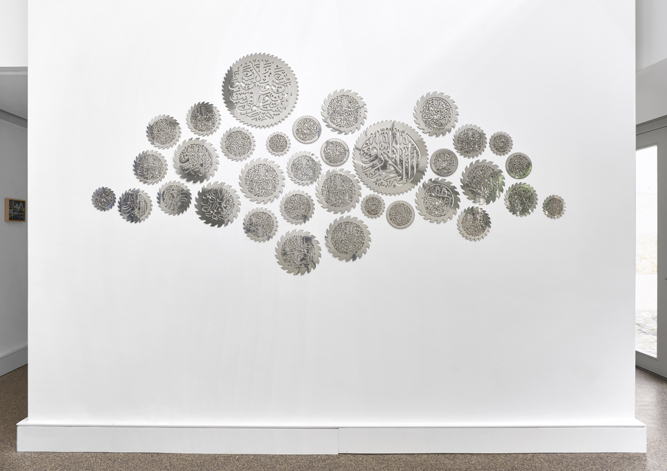

In the central gallery is Machinery, a large wall installation of thirty circular saw blades of varying diameters. The artist returns to the primitive form of the wheel as an essential element and questions the evolution of the machine from the Industrial Revolution to the information revolution. fatmi’s work routinely subverts found objects, in this case, a tool used in construction and destruction. Calligraphic inscriptions of texts from the Surah or Hadith evoke the beauty of God or man’s capacity, or desire, to obtain knowledge, are laser cut into the blades. The calligraphy’s aesthetic nature contrasts with the saws’ potential danger. One of mounir fatmi’s primary preoccupations is displaying the ambiguous beauty and violence of the machine. He argues that words are never harmless, and these more-than-menacing serrated blades could put anyone who gets too close in danger. Machinery compels viewers to confront their vulnerability to the materiality of the saw as much as the words they depict. The installation deliberately takes the form of a gear mechanism. The unrelenting and fatal wheels seem to signify some world order. If this machinery were set in motion, it would wield power to destroy, to tear to shreds. But is it the object or information it carries that is in question?

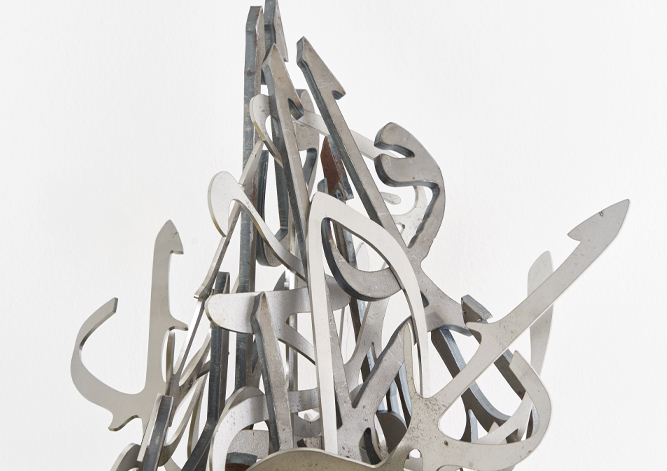

The sculpture Heavier Than Words poses different questions concerning language, the core of mounir fatmi’s artistic investigation. Made up of a classic Roberval balance, steel Arabic calligraphic motifs are piled on one end of the scale while the other tray is empty. At first, everything seems in order. However, upon closer inspection, something is off. The empty tray is heavier, while the tray filled with steel appears to float with lightness. How is this defiance of physics even possible? What does emptiness mean? Its definition seems to be hallowed. Like black matter, is it invisible yet present? This sculpture captures fatmi’s interrogation and deconstruction of language. It begs the questions of what carries more weight than words, what are the limitations of speech, and how is the power of thought undermined?

Everything is heavier than words, which by their very nature are immaterial and performative, with only as much influence as we are willing to grant them. By comparing language to emptiness, the sculpture forces the viewer to question the reality that conditions our perception of the world. mounir fatmi states, “more than anything, my interest in abstract, complex alphabets is because I found something spiritual in these elements so full of information, and that drives my inquiries and endeavors to find an answer for the absurdities of our modern world.

Wilde Gallery, September 2022 |