|

|

How to Disappear Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg March 14, 2020 – May 31, 2020 Curator: Amy Watson

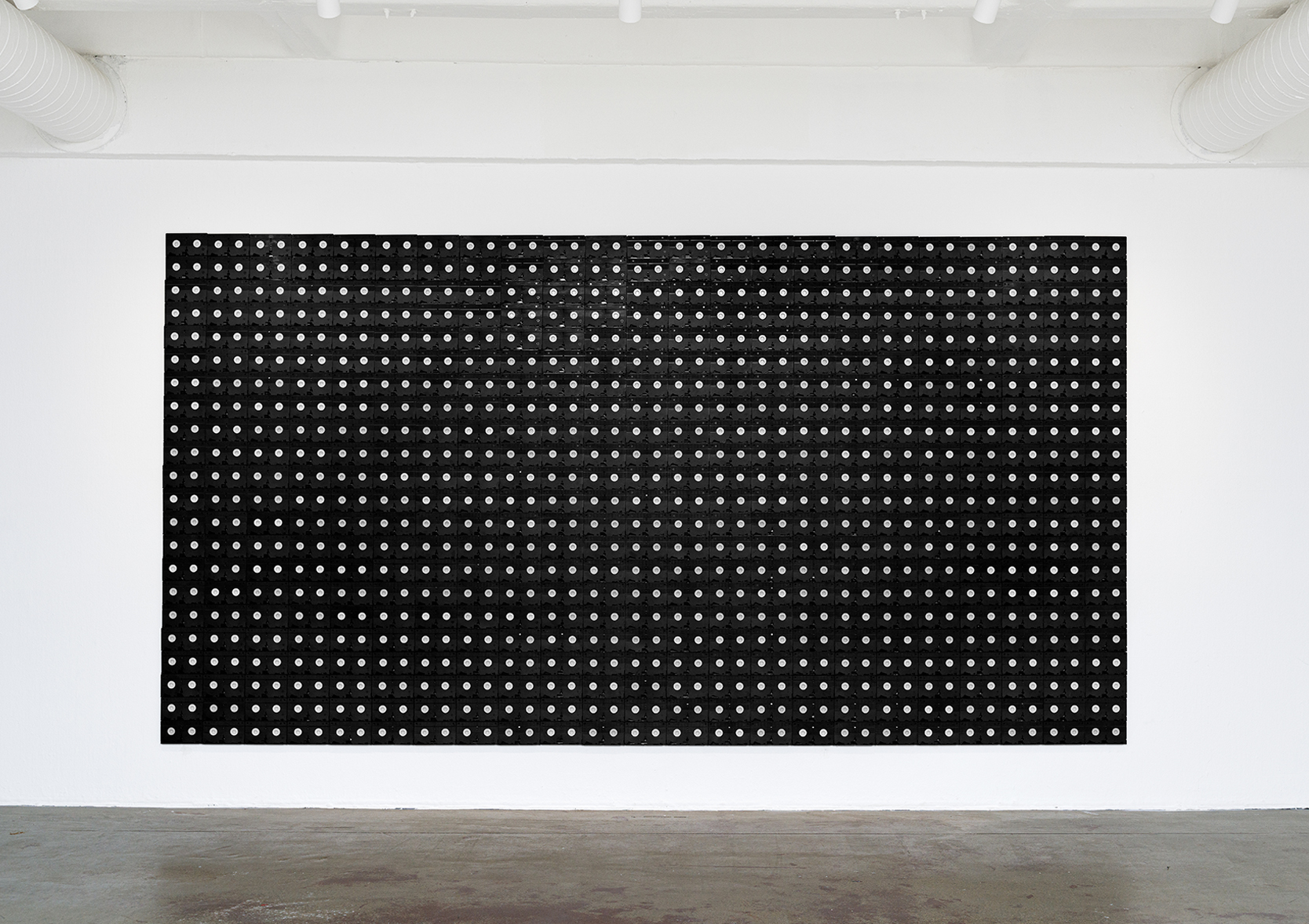

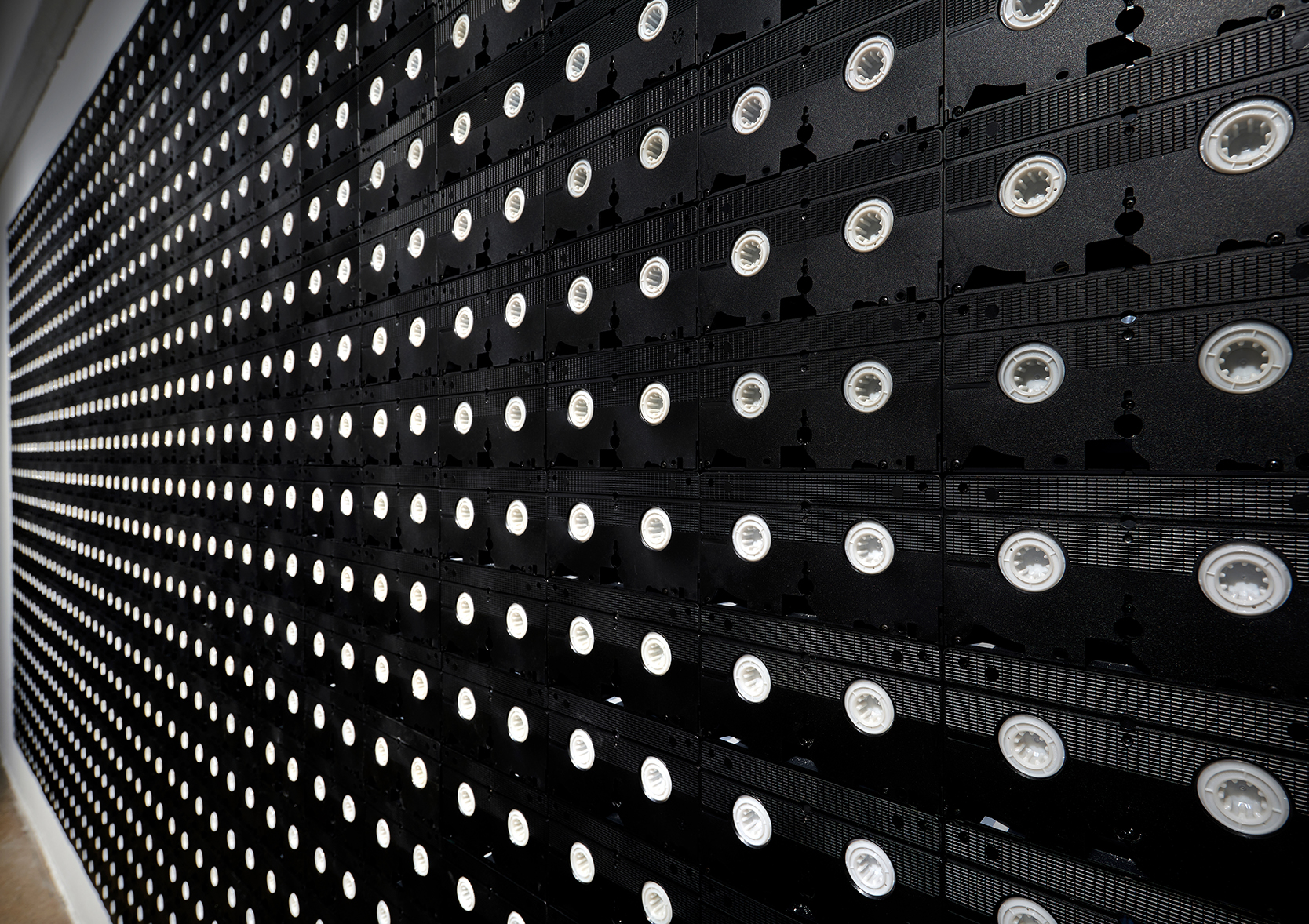

Ewa Nowak, Broomberg & Chanarin, Mary Wafer, David Goldblatt, Ja’Tovia Gary, Hyun-Sook Song, mounir fatmi, Jeremy Wafer, Kahlil Joseph and Nolan Oswald Dennis. How To Disappear considers the pervasive modes and technologies of surveillance in the making of contemporary society. This includes subtle and overt practices of racial profiling in public spaces, the distant violence of aerial surveillance, and the silent accumulation and instrumentalisation of algorithmic and digital data. Working with analogue and digital imaging technologies, found footage and photographs, and more traditional media, participating artists’ reflect on how these surveillance methods render us as visible and visualised subjects. And in some cases, attempt to reclaim a sense of autonomy by revealing how these technologies might be turned towards forms of resistance. Pernicious forms of surveillance hold a particular resonance in the contemporary moment. Globally, we’re witnessing this in the form of ‘surveillance capitalism’ – a term coined by author Shoshana Zuboff to refer to the use of human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioural data. While earlier this year, the Constitutional Court ruled that the Regulation of Interception of Communications and Provision of Communication-Related Information Act (Rica) has failed to safeguard South African’s rights to privacy. Ewa Nowak’s speculative work Incognito (2018) aims to protect the individual from facial recognition algorithms used in surveillance cameras installed in public spaces and online. These cameras are able to recognise our age, mood, or sex and precisely match us to a database. Incognito disturbs the characteristic elements of the human face, making it difficult for this technology to operate. “The object is speculative,” says Nowak, “it can be assumed that in the future it could be a kind of commonly worn jewelry.” Broomberg and Chanarin’s Anniversary of a Revolution (Parsed) (2019) reinscribes Dziga Vertov’s (1896-1954) debut film using digital technology in collaboration with London-based creative technology studio, The Workers. The film employs powerful machine-vision technology to map the physical movements from the original film onto a digital rendering using 21st century surveillance technology. The Belfast Exposed archive was founded in 1983 as a response to concern over the careful control of images depicting British military activity during the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict that took place in Northern Ireland in the late 20th Century. Drawing on this archive, Broomberg and Chanarin highlight the marks and censored sections of the photographic contact sheets. In turn, the artists reveal the presence of successive archivists and members of the public who have ordered, catalogued and defaced these photographs over the years. Mary Wafer’s research-based paintings depict John Voster Square, a modernist building implicated in numerous cases of apartheid-era abuses. In Wafer’s depictions of the building, renamed Johannesburg Central Police Station, its louvered façade appears deteriorated, reflecting the ongoing culture of systemic and institutionalised violence and intimidation in the South African Police Service. David Goldblatt’s little known photographic series While in Traffic, Johannesburg (1967) features candid images of people in their cars. These images were taken in the same year the South African Police force began counter-insurgency training. Assuming a voyeuristic perspective, Goldblatt captures his subjects in mid-conversation, gazing into the distance and glancing at other passengers. Ja’Tovia Gary’s film, An Ecstatic Experience (2015), examines the legacy of resistance by reclaiming iconic historical events with the goal of reimagining the Black figure within moving image. The film uses recuperated archival material, montage editing, and analogue animation techniques. The result is a piece of work that explores transcendence as both a means of restoration and a form of resistance. In her unique economical painting technique, Hyun-Sook Song uses semi-transparent tempera on canvas. The effect is almost transparent brushstrokes, each representing a single movement. The ‘wooden poles’ depicted in Song’s work refer to a basic form of shelter, while the fabrics she paints often suggest the ancient tradition of ramie weaving. Peripheral Vision (2017) includes four photographic portraits of mounir fatmi in which the artist’s face is partly obscured behind a large geometry protractor held at eye level. The work addresses the question of vision as a set of cognitive processes and mental operations that contribute to the perception of our environment. In this work fatmi signals the way we percieve what surrounds us and encourages a new awareness of what connects us to the world and of the comprehension of its limits. fatmi’s Black Screen (2005) appears as a large format painting constituted by VHS cassette tapes. The analogue tapes appear back-to-front beside each other, reflecting the obsolete nature of the technology, which contains what we have seen, or think we have seen, what we have been exposed to, and what remains hidden. Jeremy Wafer’s circular photographic works, Nhlube (2004/2020) and Spitzkop (2004/2020) contrast two places, one deeply familiar to the artist and the other, a non-descript view of veld. Wafer sourced these images from the South African survey office, and scanned and isolated sections using a circular template. This forms part of Wafer’s ongoing exploration of cartography and aerial survey mapping photography as a means for bringing to light the socio-political and psychological implications of the division of land in South Africa. Commenting on his practice, Wafer states: “The aerial view denies the openness or invitation to entry which is characteristic of a vista, the scanning or looking out and across space: it denies horizon, any hierarchy of foreground to background, direction or orientation, there and here. The affect of this looking down is somewhat oppressive and claustrophobic.” Khalil Joseph’s BLKNWS (2019) redefines the genre of the news broadcast. BLKNWS consists of a continuously updated newscast of black life in America in the form of a two-channel video that splices historical and contemporary found footage with newly shot scenes of news room and documentary reportage. Each broadcast is shown on two adjacent screens that play simultaneous footage meant to inflect and inform each other in a continuous dialogue. Through Joseph’s use of juxtaposition and montage, _BLKNWS_ both comments on the inherent bias of the news-industrial complex by creating an editorial voices that approaches reportage through a distinctly black lens. Nolan Oswald Dennis’ works Aporia (2016) are monoliths of light wrapped in grey utility blankets. The work is inspired by the interim state experienced during cycles of political contestation. Dennis points to the example of Chumani Maxwele’s fecal protest of the Cecil Rhodes statue in Cape Town, which lead to its removal by the University. “The statue was first wrapped in plastic and then boxed in plywood while the university attempted to respond to the decolonial demand of the students,” states Dennis. “This moment of half-removal, or attempting to conceal the issue, creates a suspension in the political process, an attempt to both remove and not remove the offending object. In much the same way these works attempt to both share and conceal the light which is their operative function by covering them with utility blankets – a material associated with the protection and mobility of human bodies as well as objects. Aporia are monoliths with an irresolvable double agenda in that they are both physically imposing and functionally meek. This sculptural cycle is reaching toward a (South) African non-object, a language for postponement and deferral.”

Amy Watson, March 2020 |