| |

|

07.

| Sculpture sequence : The Machinery

| Sculpture sequence : The Machinery |

| |

'' « The Machinery » is an optical device translating both an operation of visual seduction and the difficulty to see and understand

the true meaning of the message that tends to be concealed in the stylized ornamentations of a powerful rhetorical apparatus. ''

Studio Fatmi, September 2017

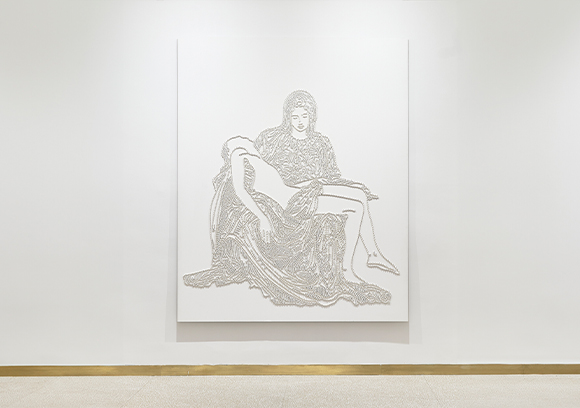

La Pieta

Exhibition view from If you don't know me by now, Ceysson & Bénétière, 2024, Lyon.

La Pieta

Exhibition view from If you don't know me by now, Ceysson & Bénétière, 2024, Lyon.

La Pieta

Exhibition view from If you don't know me by now, Ceysson & Bénétière, 2024, Lyon.

La Pieta

Exhibition view from #Cometogether, Edge of Arabia, 2012, London.

La Pieta

Exhibition view from #Cometogether, Edge of Arabia, 2012, London.

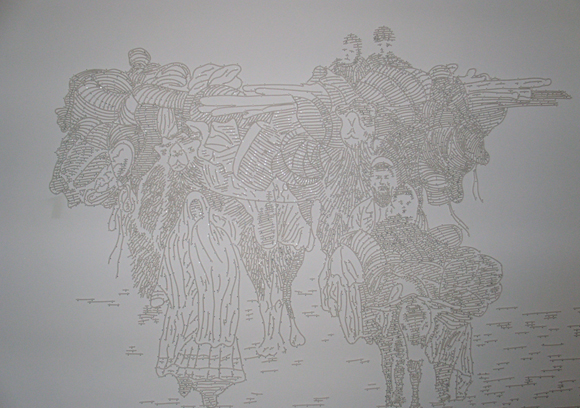

The Machinery

Exhibition view from Art Brussels, Conrads Gallery, 2010, Brussels.

People know, people don't know

Exhibition view from Jusqu'au bout de la poussière, Espace des arts, 2004, Colomiers.

Al Jazeera

xhibition view from Looking at the World Around You, Santander Art Gallery, 2016, Madrid.

Presumed Innocent

Exhibition view from Icons, Fondation Boghossian, 2021, Brussels.

Kabul

Exhibition view from Comprendra bien qui comprendra le dernier, CAC Le Parvis, 2004, Ibos.

|

|

2008, coaxial antenna cable on wood panel, staples, plexiglas, 150 cm x 5 cm.

Exhibition view from Art Brussels, Conrads Gallery, 2010, Brussels.

Courtesy of the artist and Ceysson & Bénétière, Paris.

Ed. of 5 + 1 A.P.

|

|

|

| Collection of Nadour, Krefeld

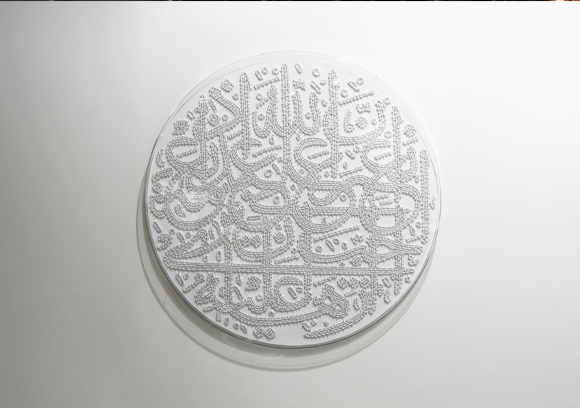

Bas-relief circulaire au large diamètre, « The Machinery » est réalisé au moyen de câbles coaxiaux, matériau régulièrement utilisé par mounir fatmi dans ses œuvres, et outil de transmission des images et de l'information principalement employé jusqu'à la fin des années quatre vingt dix. Fixées à un panneau de bois blanc, les sections de câbles sont assemblées en motifs calligraphiques en arabe classique et reprennent un hadith du prophète : « Dieu aime voir les traces de ses bienfaits sur ses serviteurs ».

Exégèse artistique de la citation religieuse, l'œuvre explore les rapports de la religion à la possession de biens matériels et à la richesse. « The Machinery » examine l'inscription du discours religieux au sein des formes contemporaines d'organisations sociales, fortement marquées par le capitalisme, la production en masse de biens matériels, le commerce et la consommation. La sculpture tente ainsi de définir la relation de l'œuvre d'art à sa valeur commerciale et à la société marchande. Le bas-relief mis au point par mounir fatmi est un dispositif aux inspirations multiples dont la stratégie se fonde sur les connexions. Il relie entre eux les rotoreliefs de Duchamp - qui eux-mêmes, à l'origine, font se rencontrer les techniques du monde industrialisé et celles de l'art contemporain - le dripping et le all over de Pollock, l'artisanat religieux, les réflexions de linguistes enfin et celles de philosophes au sujet de la production des significations, des valeurs et des objets.

Le dispositif optique de « The Machinery » rend compte à la fois d'une opération de séduction visuelle et d'une difficulté à voir et à comprendre le véritable sens du message émis qui tend à se dissimuler dans les ornementations stylisées d'un puissant appareil rhétorique. L'œuvre appelle à une méditation visuelle et à un effort de discernement de la part du spectateur, censé se prolonger au-delà des apparences. Elle lui donne à observer les effets d'un discours religieux, séducteur, affirmatif et péremptoire. Elle reproduit les mécanismes d'une machine expressive dont la fonction est de confirmer et d'assurer le pouvoir des puissants. Un autre hadith affirme que « La pauvreté extrême avoisine la mécréance ». Il semble dire que Dieu, de façon fort peu compatissante et quelque peu paradoxale, refuse même le secours de la foi aux misérables qu'il met pourtant à l'épreuve… Elle constitue une illustration du fait que le discours religieux a pour fonction essentielle la justification de la domination historique des puissants et des riches sur les pauvres.

L'amour de Dieu pour les signes extérieurs de richesse évoqué par le premier hadith valide une société des apparences et du matérialisme où la question de la possession prime sur celles des qualités humaines. L'accumulation sans partage des richesses et la hiérarchie sociale qui oppose riches et pauvres se voient ainsi justifiées. L'œuvre d'art refuse pour sa part de se soumettre à un pouvoir arbitraire et prend le partie d'une démarche critique et d'une déconstruction de la machinerie du discours religieux. Avec le recours à un matériau « pauvre » tel que le câble coaxial, dont la simplicité contraste avec la richesse des ornementations calligraphiques et religieuses, l'œuvre d'art semble, avec une pointe d'ironie, faire vœux de pauvreté tout en réservant une voie d'accès privilégiée à l'art et au sacré pour son humble spectateur.

Studio Fatmi, Septembre 2017.

|

|

A circular, large diameter bas-relief, « The Machinery » was created with coaxial cables, a material frequently used by mounir fatmi in his work, and a tool for the transmission of images and information that was widely used until the late 1990s. Fixed to a white wood panel, the sections of cable are assembled into calligraphic motifs in classic Arabic reproducing one of the prophet’s hadiths: « God loves to see the signs of his blessings on his servants ».

The work is an artistic exegesis of this religious quote, and it explores the relation of religion to the possession of material goods and wealth. « The Machinery » examines how religious discourse fits into our contemporary forms of social organization that are strongly affected by capitalism, the mass production of material goods, commerce and consumption. In doing this, the sculpture tries to define the relation of a work of art to its commercial value and to the market society. The bas-relief created by mounir fatmi is a device with multiple aspirations whose strategy is based on connections. It connects Duchamp’s rotoreliefs to each other – they themselves originally combined industrial techniques with those of contemporary art – to Jackson Pollock’s dripping and all-over, together with religious craftsmanship and research in linguistics and philosophy on the creation of significations, values and objects.

« The Machinery » is an optical device translating both an operation of visual seduction and the difficulty to see and understand the true meaning of the message that tends to be concealed in the stylized ornamentations of a powerful rhetorical apparatus. The piece appeals to a visual meditation and an effort of discrimination on the part of the viewers, who are encouraged to go beyond appearances. It shows them the effects of a religious discourse that is seductive, affirmative and peremptory. It reproduces the mechanisms of an expressive machine whose function is to confirm and assert the powers that be. Another hadith states that « extreme poverty verges on disbelief ». It seems to say that God, in a somewhat uncompassionate and paradoxical attitude, refuses salvation through faith to the destitute, while at the same time he puts them to the test… This illustrates the fact that the main function of religious discourse is to justify the historical domination of the rich and powerful over the poor.

God’s love for external signs of wealth evoked in the first hadith validates a society based on appearances and materialism, where the subject of possessions takes precedence over that of human qualities. The accumulation of wealth without sharing and the social hierarchy opposing rich and poor are thus justified. As for the work of art, it refuses to submit to an arbitrary power and opts for a critical approach and the deconstruction of the machinery of religious discourse. Recurring to a « poor » material such as coaxial cable, whose simplicity contrasts with the richness of ornamental and religious calligraphy, the piece seems, with a touch of irony, to make a vow of poverty while granting its humble viewers a priority access to art and the sacred.

Studio Fatmi, September 2017. |

|

|

|