| |

|

|

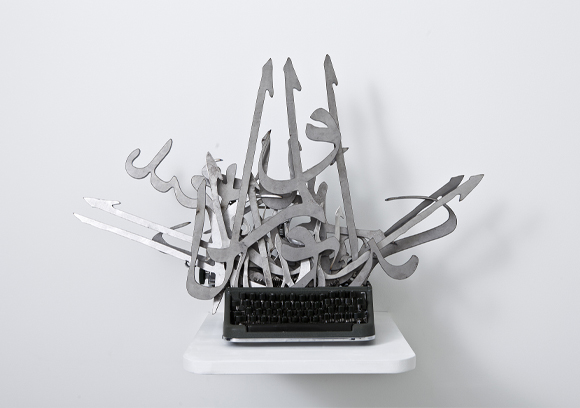

28.

| The Impossible Union |

| |

2011, arabic calligraphies of steel, hebrew typewriter.

Exhibition view from The Angel's Black Leg, Conrads Gallery, 2011, Düsseldorf.

Courtesy of the artist and Ceysson & Bénétière, Paris.

Ed. of 5 + 1 A.P.

'' An amazing collision of Western modernity and Islamic traditionalism that nevertheless evokes unavoidable associations with historical and current political events. ''

Barbara Til, 2013

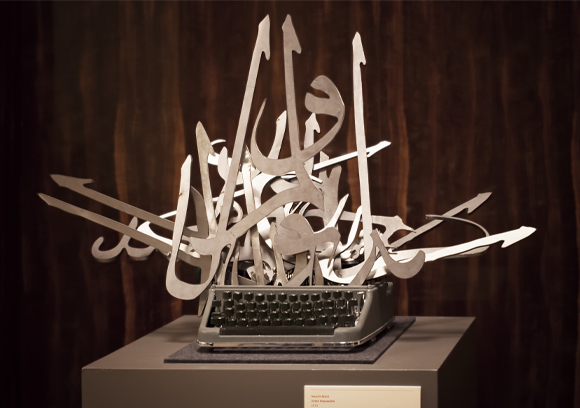

The Impossible Union

Exhibition view from Intersections, Keitelman Gallery, 2013, Brussels.

The Impossible Union

Exhibition view from Between two stools, one book, Fondation Boghossian, 2014, Brussels.

|

|

|

|

|

| Collection of Kunst Palast Museum, Düsseldorf

Collection of Galila's P.O.C., Brussels

<"Mais pour nous, l’art est tout ce que nous trouvons qui porte ce nom. Quelque chose qui n’est pas gouverné par des lois, quelque chose qui est un produit complexe de la société."

Cette citation de l’écrivain autrichien Robert Musil, dans laquelle il fait référence à la construction sociale et par conséquent à la composante sociale de l’art, s’applique parfaitement à la « machine à écrire » de Fatmi, parce que cette œuvre trouve sa concrétisation artistique dans le mélange de trois cultures dans l’esprit du spectateur et, de façon concomitante, dans l’inévitable engagement politique qui l’accompagne.

Au premier abord, ce qu’on voit c’est une machine à écrire vieillote, mécanique et de couleur vert militaire, d’où des lettres arabes jaillissent comme des flammes. Mais, en regardant de plus près ce que Fatmi a ici conçu à la façon d’un ready-made, la surprise s’accroît face à la nature a priori paradoxale de cette combinaison : une machine à écrire avec des caractères hébreux, le nom du fabricant allemand Olympia Werke West GmbH inscrit sur l’avant. Cela évoque des réflexions sur le passé – la machine à écrire occidentale en tant que reliquat d’une époque remémorée mais techniquement dépassée. Et à l’endroit où les branches métalliques devraient normalement entrer en contact avec le papier, une calligraphie arabe sophistiquée en tant qu’expression ornementale de la culture orientale qui semble véritablement pulvériser le temps et l’espace – une collision impressionnante de la modernité occidentale et du traditionalisme islamique qui évoque forcément des événements historiques autant que des problématiques actuelles. On ne peut s’empêcher de penser aux conflits au Moyen Orient, à la relation irréconciliable entre Israël et Palestine et, au bout du compte, à la Shoah.

Dans ses peintures, sculptures, photographies, films et installations invariablement percutants, Mounir Fatmi revient sans cesse sur ces références à multiples niveaux situées entre Orient et Occident, ainsi que sur les changements culturels et politiques et les poudrières qui y sont associés. Né en 1970 à Tanger, une ville qui a de tout temps été considérée comme un lieu ou les cultures maghrébine et occidentale se mêlent, Fatmi vit et travaille entre Paris et Tanger. Activement engagé dans le débat social et artistique dans les deux villes, il endosse le rôle de l’artiste en tant qu’étranger dans des contextes culturels différents. Il voit ainsi la question de la relation à l’« Autre » - celui qui existe prétendument hors de sa culture à soi, hors de la compréhension qu’on a de soi-même – comme le principal point de départ de son art. Parallèlement, le thème de l’Union impossible est à la fois éminemment politique et existentiel. Fatmi fait ici une référence subtile, autant sémantiquement que par le contenu, au réseau complexe de relations qui existent entre les cultures juive, chrétienne et arabe : la machine à écrire aux caractères hébreux signifie la précision, mais aussi la violence et l’oppression ; les caractères arabes métalliques soulignent la signification du mot, et en réalité la force du mot ; et enfin le titre de l’œuvre peut soit être compris comme une question, soit comme une harangue pour que nous agissions, que nous nous engagions.

Sans aucun doute, l’œuvre tire sa puissance de l’expressivité même de la calligraphie arabe, qui est traditionnellement liée au Coran, car la parole divine dans l’Islam fut dite et retranscrite en arabe. La relation intime entre la religion et la parole écrite entoure la langue arabe d’une sorte de nimbe, ce qui fait que la calligraphie peut être en quelque sorte comprise comme une forme de représentation allusive – « on l’aborde comme on aborderait une peinture et une œuvre isolée ». Qui plus est, l’écriture arabe appartient à l’art islamique classique et possède – au même titre que sa signification contextuelle – une fonction esthétique, avec des possibilités graphiques diverses qui sont déployées dans l’art contemporain oriental mais aussi occidental. Fatmi – en tant qu’individu qui met en place l’œuvre – utilise le champ de la calligraphie dans l’Union impossible en combinant les lettres de façon aléatoire pour créer des signes esthétiques et même des mots, en sachant parfaitement que l’esthétique ornementale de l’arabe recèle une certaine ambiguïté, en l’occurrence la force et la beauté d’une œuvre ornementale dotée d’un message sémantique qui peut être à la fois terrifiant et incroyablement douloureux. Ainsi, le travail de Fatmi peut être compris autant dans le sens d’une injonction pour promouvoir la tolérance, le progrès et la connaissance que comme un combat en faveur de la beauté, de la divinité et de l’humanité, mais aussi la quête d’un chemin qui soit partagé par la modernité occidentale et la tradition islamique.

Barbara Til, Museum Kunst Palast, Düsseldorf 2013 ©Barbara Til + CONRADS Düsseldorf

|

|

“But for us, art is what ever we find that goes by that name. Something not governed by laws, something that is a complicated social product.”

This statement by the Austrian writer Robert Musil, in which he refers to the social construction and thereby the social component of art, can definitely be applied to Fatmi’s “typewriter work”, because the work ultimately finds its artistic fulfilment via the conflation of three cultures in the mind of the viewer and, concomitantly, the unavoidable political engagement therewith.

At first glance, what you see is an old-fashioned, mechanical, military-green coloured typewriter, out of which metal Arabic letters dart forth like flames. However, upon closer inspection of what Fatmi has fashioned here in the manner of a ready-made, our surprise about the seemingly paradoxical nature of this combination grows: a typewriter with Hebrew type, the German manufacturer’s name Olympia Werke West GmbH emblazoned across the front. It conjures up thoughts about the past – the Western typewriter as a relic of a remembered, but technically outmoded epoch. And in the place where the metal type would normally connect with the paper, there is florid Arabic calligraphy as an ornamental painterly expression of Oriental culture which veritably seems to explode time and space – an amazing collision of Western modernity and Islamic traditionalism that nevertheless evokes unavoidable associations with historical and current political events. Thoughts about the conflicts in the Near and Middle East force themselves to the surface, about the irreconcilable relationship between Israel and Palestine and, ultimately, about the Holocaust.

In his invariably incisive paintings, sculptures, photographs, films and installations, Mounir Fatmi repeatedly focuses thematically upon these multilayered references situated between the spheres of East and West, as well as the associated cultural and political changes and flashpoints. Fatmi, born in 1970 in Tangiers, Morocco – since time immemorial, a city that has been considered a place where Maghrebian and Western cultures coalesce – lives and works in Paris and Tangiers. Actively engaged in the current social and artistic discourse in both localities, he takes up the position of the artist as a stranger within respective cultural contexts. Thus, he sees the question relating to the relationship with the ‘Other’ – the one who supposedly exists outside one’s own culture, one’s own cultural self-understanding – as the key point of departure for his art. Correspondingly, the theme of The Impossible Union is both highly political and existential at the same time. Fatmi is subtly referring here, both semantically and in terms of content, to the complex network of relationships between Jewish, Christian and Arab cultures: the German typewriter with Hebrew type, which stands for precision, but also violence and oppression; the metal Arabic symbols that highlight the meaning of the word, indeed, the power of the word; and the work’s English title, which can be understood as a question and /or an entreaty for us to act, to engage.

Undoubtedly, the work obtains its incisiveness through the very expressivity of the Arabic calligraphy, which is traditionally closely related to the Koran, as the word of God in Islam was spoken and recorded in Arabic. The close connection between religion and the written word surrounds Arabic with a kind of ‘nimbus’ and consequently, the calligraphy can be understood as a form of allusive representation, as it were – “one approaches it as one would an isolated painting and artwork”. In addition, Arabic script belongs to classical Islamic art and has – along with its contextual meaning – an aesthetic function, the diverse graphic possibilities of which are deployed in contemporary Oriental as well as in Western art. Fatmi – that is to say, the person who sets the work up – uses the scope of the calligraphy in The Impossible Union by combining the individual letters randomly to create aesthetic signs or even words, in the knowledge that the ornamental aesthetic of Arabic definitely contains a certain ambiguity, namely the power and beauty of an ornamental work endowed with a semantic message which can be simultaneeously terrifying and agonizingly painful. Thus, Mounir Fatmi’s work can be understood both in the sense of dictum promoting more tolerance, enlightenment and insight, and indeed as an engagement concerned with beauty, divinity and humanity, as well as with the quest for a joint path somewhere between Western modernity and Islamic tradition.

Barbara Til, Museum Kunst Palast, Düsseldorf 2013

Translation: Tim Connell

©Barbara Til + CONRADS Düsseldorf

|

|

|

|