| |

|

37.

| Who needs a god triangle? 03

| Who needs a god triangle? 03 |

| |

'' Who Needs a Triangular God? contributes to the elaboration of an attractive esthetic with the paradoxical objective of delivering a lesson on the dangerous seductiveness of images. ''

Studio Fatmi, February 2017

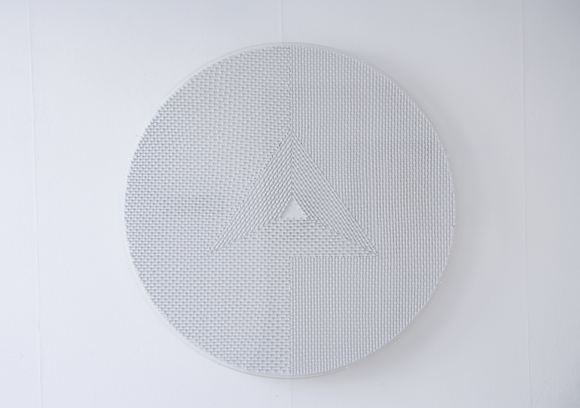

Who needs a god triangle? 01

Exhibition view from Constructing Illusion, Analix Forever, 2015, Paris.

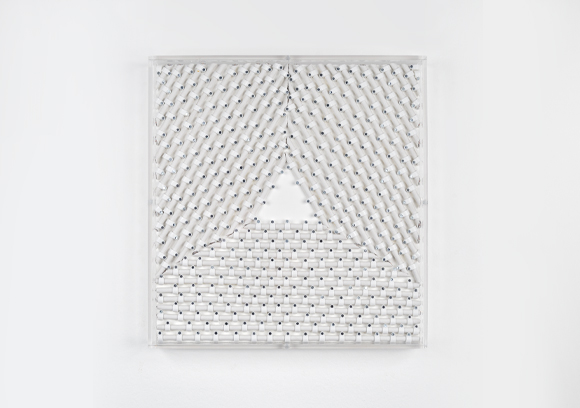

Who needs a god triangle? 03

Exhibition view from Constructing Illusion, Analix Forever, 2015, Paris.

|

|

2013, 35 x 37 cm, coaxial antenna cable, staples, plexicase.

Courtesy of the artist and Ceysson & Bénétière, Paris.

|

|

|

|

Qui a besoin d'un Dieu Triangle? joue avec les perceptions à la manière d'une illusion d'optique. La sculpture blanche se confond avec les murs blancs et disparaît progressivement dans le décor. Son aspect plat et uniforme est une illusion également et la surface irrégulière est en réalité composée de sections de câbles coaxiaux à gaine blanche - matériau utilisé jusqu'à la fin du 20e siècle pour relier une antenne à un téléviseur et transmettre des images - rassemblés selon différents angles, puis épinglés sur un panneau blanc de telle sorte qu'ils laissent apparaître une surface triangulaire non recouverte au centre de la composition.

Qui a besoin d'un Dieu Triangle? aborde un problème théologique ancestral : comment parler de Dieu ? Que dire de Dieu ? L'œuvre interroge la nature du divin dans nos sociétés et explore ses représentations à travers les sociétés et les époques. Elle tente également de définir les rapports entretenus entre l'art et le sacré. Qui a besoin d'un Dieu Triangle ? revisite ainsi le bas-relief en tant qu'élément architectural caractéristique de l'art religieux, au moyen des techniques de l'art contemporain, inspirées du dripping, du all over et de l'abstraction géométrique. L'œuvre mime une scène de révélation d'un sens ésotérique et tente une représentation de l'invisible et de l'ineffable. Son titre, en forme de question rhétorique, fait malicieusement allusion aux nombreux débats théologiques que l'Occident a connu depuis le Moyen Age sur la question de la représentation du divin. Montesquieu faisait par exemple dire à son personnage dans les Lettres Persanes : "Si les triangles faisaient un Dieu, ils lui donneraient trois côtés". Spinoza écrivait dans une lettre adressée à un contradicteur : « si le triangle avait la faculté de parler, j’estime qu’il dirait : « Dieu est éminemment triangulaire » ; et le cercle dirait également, par une raison éminente, que la nature divine est circulaire ; et, ainsi, chaque chose affirmerait de Dieu ses attributs propres, et se rendrait semblable à lui. »

Qui a besoin d'un Dieu Triangle? met en évidence la relativité des représentations du divin et décompose les processus à l'œuvre dans leur élaboration. L'œuvre pointe du doigt la dimension collective des significations - le choix des câbles coaxiaux insiste sur la circulation de l'information et les connexions réalisées - dont l'établissement est essentiellement affaire de consensus social. Elle montre également comment un système peut cultiver à loisir la complexité. Son dispositif expérimente les phénomènes de projection à l'œuvre dans les processus de perception, en permettant au spectateur d'interpréter librement la composition générale comme une simple proposition géométrique ou comme un symbole religieux. L'œuvre d'art quant à elle tend à s'éloigner du domaine du sacré, à prendre ses distances par rapport à lui, pour mieux en exposer les mécanismes. Elle interroge les dogmes, les consensus et les stéréotypes sociaux. Elle questionne nos représentations mentales en les mettant à distance. Elle désacralise et révèle la part de projections et d'anthropomorphismes, tout en mettant en garde contre les raisonnements et justifications qui ne sont parfois que ratiocinations. Quant à vouloir déterminer la nature du divin dans nos sociétés, peut-être faut-il aller chercher du côté des nouvelles technologies… "Dieu est le pus grand des spectacles" déclare Mounir Fatmi dont les œuvres s'inspirent notamment de Debord et de ses écrits sur la société de consommation.

Qui a besoin d'un Dieu Triangle? participe à l'élaboration d'une esthétique séductrice dans le but, paradoxalement, de délivrer une leçon sur la séduction des images et ses dangers. Alors que le bas-relief invite le spectateur à recevoir en silence la signification de l'œuvre, Mounir Fatmi propose au spectateur de réfléchir activement aux processus qui interviennent dans la formation des significations et des représentations mentales.

Studio Fatmi, Février 2017.

|

|

Who Needs a Triangular God? meddles with perceptions like an optical illusion would. The white sculpture blends with the white walls and progressively disappears in its surroundings. Its flat and uniform aspect is also an illusion as its irregular surface is actually composed of pieces of white sheathed coaxial cable – a material used up to the end of the 20th century to connect an antenna to a television and transmit images – grouped together at varying angles and pinned to a white board in such a way that they reveal an uncovered triangular surface in the center of the composition.

Who Needs a Triangular God? addresses an age-old theological issue: how can one speak of God? What can be said about God? The work questions the nature of the divine in our societies and explores its representations through societies and epochs. It also tries to define the relations between art and the sacred. In that perspective, Who Needs a Triangular God? revisits the bas-relief as an architectural element characteristic of religious art by way of contemporary art techniques inspired by dripping, all-over and geometric abstraction. The work mimics a scene of revelation in an esoteric sense and attempts to represent the invisible and unspeakable. Its title, in the form of a rhetorical question, mischievously alludes to the numerous theological debates the Western civilization has experienced since the Middle Ages regarding the question of the representation of the divine. Montesquieu for instance had one of his characters in “The Persian Letters” say: “If triangles created a God, they would give him three sides”. Spinoza wrote in a letter to a contradictor: “If a triangle could speak, I believe it would say: ‘God is eminently triangular’ and the circle would also say, with brilliant reasoning, that the divine nature is circular; and thus, all objects would claim that God possesses their own attributes and resembles them.”

Who Needs a Triangular God? stresses the relativity of the representations of the divine and deconstructs the processes that underlie their elaboration. The work aims to underline the collective dimension of significations – the choice of coaxial cables insists upon the circulation of information and the connections it creates – that are essentially established according to social consensus. It also shows how a system can endlessly cultivate complexity. Its configuration experiments with the phenomena of projection at play within processes of perception by allowing the viewer to freely interpret the general composition as a simple geometric proposition or as a religious symbol. The work of art itself tends to move away from the realm of the sacred and distance itself from it, in order to better understand its mechanisms. It questions dogma, consensus and social stereotypes. It also questions our mental representations by keeping them away. It desacralizes and reveals the proportion of projections and anthropomorphism, while issuing a warning against arguments and justifications that are sometimes nothing more than ratiocinations. As for wanting to determine the nature of the divine in our societies, perhaps we should look to modern technology… “God is the greatest of shows”, says Mounir Fatmi whose work draws inspiration from Guy Debord and his writings on the consumer society.

Who Needs a Triangular God? contributes to the elaboration of an attractive esthetic with the paradoxical objective of delivering a lesson on the dangerous seductiveness of images. While the bas-relief invites the viewer to quietly receive the work’s signification, Mounir Fatmi urges him to actively reflect upon the processes that are at play in the formation of significations and mental representations.???

Studio Fatmi, February 2017.

|

|

|

|