| |

|

|

07.

| Face |

| |

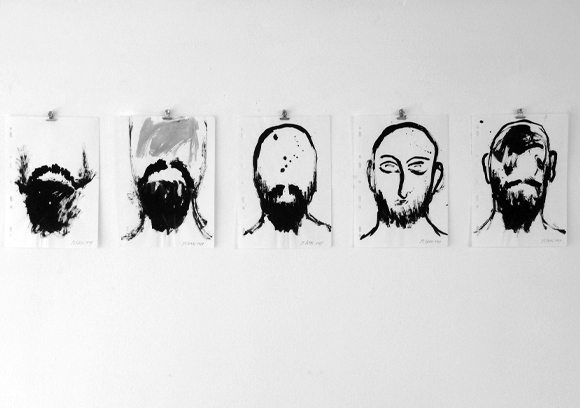

1999, serie of 13 drawings, ink and acrylic on paper, 21 x 29,7 cm.

Exhibition view from Blinding Light, Analix Forever, 2013, Geneva.

Courtesy of the artist.

1999, serie of 13 drawings, ink and acrylic on paper, 21 x 29,7 cm.

Exhibition view from Blinding Light, Analix Forever, 2013, Geneva.

Courtesy of the artist.

1999, serie of 13 drawings, ink and acrylic on paper, 21 x 29,7 cm.

Exhibition view from Blinding Light, Analix Forever, 2013, Geneva.

Courtesy of the artist.

1999, serie of 13 drawings, ink and acrylic on paper, 21 x 29,7 cm.

Exhibition view from Blinding Light, Analix Forever, 2013, Geneva.

Courtesy of the artist.

1999, serie of 13 drawings, ink and acrylic on paper, 21 x 29,7 cm.

Exhibition view from Blinding Light, Analix Forever, 2013, Geneva.

Courtesy of the artist.

'' The mechanisms of recognition are illustrated through portraits using a drastically reduced plastic vocabulary. The drawings are halfway between minimalism and figuration and experience the limits of cognitive and intellectual processes. ''

Studio Fatmi, May 2018

Face

Exhibition view from Blinding Light, Analix Forever, 2013, Geneva.

Courtesy of the artist.

Face

Exhibition view from Blinding Light, Analix Forever, 2013, Geneva.

Courtesy of the artist.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inscrites dans une série de dessins à l'acrylique employant les couleurs noire, blanche et rouge, les œuvres regroupées sous le titre « Face » tracent en quelques coups de pinceaux énergiques la forme plus ou moins complète d'un visage, en isolant parfois certains de ses éléments ou détails anatomiques. Le contour d'une figure affublée d'une barbe apparaît en noir sur fond blanc et inversement. La barbe se teinte progressivement de rouge. Les organes sensoriels du personnage représentés apparaissent les uns après les autres : nez, bouche, oreilles, yeux, et tendent à devenir indistincts à mesure que le fond des compositions s'obscurcit.

Le terme « face » désigne en anatomie la partie antérieure de la tête. Son importance dans les échanges sociaux est signalée par de nombreuses expressions et dans diverses langues. L'étymologie et le sens de locutions telles que "perdre la face" ou "sauver la face" relient l'anatomie du sujet à la question de sa sauvegarde et de son intégrité. Les dessins de la série « Face » questionnent l'identité, thème essentiel dans le travail de mounir fatmi et traité dans de nombreuses œuvres, telles que les performances « Mal de Frontières » et « Barman », ou les sculptures « Coma », où sont étudiés les signes qui composent son identité d'artiste et leur perception par le public. Les dessins explorent les mécanismes qui entrent dans la constitution d'une identité et son appréhension par l'autre. Combien faut-il de traits pour composer un visage ? Sur quels éléments s'appuie la reconnaissance ?

Les mécanismes de la reconnaissance sont mis en évidence au moyen de portraits réduisant leur vocabulaire plastique de manière drastique. Les dessins se tiennent à mi-chemin entre minimalisme et figuration et expérimentent les limites des processus cognitifs et intellectuels. Le choix de la représentation tient de la litote : elle en dit le moins afin d'en dire le plus. Très peu de motifs entrent dans ces compositions, et il y aurait pourtant tant de choses à dire à leur sujet. Les motifs peuvent être lus et interprétés comme des marques du genre (la barbe associée au masculin), d'appartenance ethnique ou encore sociale. L'économie radicale des moyens de la représentation révèle des archétypes cognitifs, des traits distinctifs primaires. Elle touche à l'origine de nos perceptions et de nos représentations mentales. Elle en dit long finalement sur notre rapport au corps, à l'identité comme concept, ou à la question du genre sexuel. Les coups de pinceaux brusques, les jeux des contrastes entre noir et blanc et entre abstrait et figuratif, dramatisent la question identitaire et révèlent les dichotomies de nos représentations mentales, et traduisent également leur violence. Les questions liées au genre, à l'appartenance sociale ou ethnique sont en effet à l'origine de crispations et de conflits sociaux partout dans le monde. Les portraits appartenant à la série « Face » restent cependant suffisamment ouverts aux interprétations qu'elles veulent susciter chez le spectateur et permettent une réflexion sur la naissance de ces significations.

Studio Fatmi, Mai 2018.

|

|

Part of a series of acrylic drawings using the colors black, white and red, the pieces grouped under the title “Face” trace with just a few vigorous brush strokes the more or less complete form of a face, sometimes focusing on certain elements or anatomical details. The outline of a bearded face appears in black on a white background, and vice versa. The beard is progressively tinged with red. The character’s sensory organs appear one after the other – nose, mouth, ears, eyes – and tend to become indistinct as the background grows darker.

In anatomy, the word “face” designates the frontal part of the head. Its importance in social interactions is highlighted through many expressions in various languages. The etymology and the meaning of expressions such as “to lose face” or “to save face” link the subject’s anatomy to the question of his safeguard and integrity. The drawings from the “Face” series question identity, an essential theme in Mounir Fatmi’s work, touched upon in many of his pieces such as the performances “Border Sickness” and “Barman” or the sculptures “Coma”, where the signs that compose the artist’s identity are scrutinized, along with their perception by the public. The “Face” drawings explore the mechanisms that are part of the construction of an identity and its perception by others. How many brush strokes do you need to compose a face? On what elements is recognition based?

The mechanisms of recognition are illustrated through portraits using a drastically reduced plastic vocabulary. The drawings are halfway between minimalism and figuration and experience the limits of cognitive and intellectual processes. The choice of this type of representation is a litotes: it says less in order to express more. Very few motifs comprise these compositions, yet there is so much that could be said about them. The motifs can be read and interpreted as gender markers (the beard associated with masculinity), ethnicity or social status. The radical scarcity of means used for these representations reveals cognitive archetypes, primal distinctive features. It is linked to the very origin of our perceptions and mental representations. Ultimately, it says a lot about our relation to our bodies, to identity as a concept and to the question of gender. The brisk brush strokes and the play on contrasts, between black and white and between abstract and figurative, dramatize the question of identity and reveal the dichotomies in our mental representations, but also convey their violence. Indeed, questions related to gender, social status and ethnicity are the root of tensions and social conflict everywhere around the world. But the portraits in the “Face” series remain sufficiently open to interpretation by the viewer, enabling a reflection upon the origin of these significations.

Studio Fatmi, May 2018.

|

|

|

|